Eons ago, back in October 2016, the painter David Salle put out a book, How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking About Art. It did not enter my consciousness that this book existed until February, when I saw it displayed on the New Non-Fiction shelf at the library where I work, and I thought to myself, oh, what an ugly book, noting with distaste the blobby, glibly ingratiating computer-simulated-magic-marker-fast-food-franchise-font used for the title, primary red and blue on acid white, the words out of order in service of a visual pun: 2. to, 1. How, 3. See. The author’s name in the same kitschy mass-market font, soft gray, smaller print, in the upper right, to the right of the title’s “to,” the placement conspicuous in its self-aware awkwardness. Then I scowled, obliged to recall David Salle had not ceased to exist. I have not read his book and I do not intend to. I did read the publisher’s description – “Internationally renowned painter David Salle’s incisive essay collection illuminates the work of many influential artists of the twentieth century.” – and a review written in the New York Times: “It’s serious but never solemn, alert to pleasure, a boulevardier’s crisp stroll through the visual world.” A boulevardier, I confirmed, is a “a wealthy, fashionable socialite,” someone with the resources to spend a significant portion of his time ambling along boulevards, in that languorous Parisian way, preferably in a top coat, kidskin gloves. According to the Times, if you are grateful to be talked down to in “witty” and “sunny” tones by such a man as he heaps kudos on the art of other rich men, his upper-crust friends, you will enjoy How to See, especially if you are so grateful for a moment’s idyll in the dazzling headspace of the aristocrat as to overlook repetitiveness, shallow analysis, and lack of original insight. Isn’t it fascinating enough to learn that Urs Fischer sups daily on delicious organic fare come lunchtime? In which tell-all essay, one wonders, will we get the official scoop on Jeff Koons’ squash game? May the circle jerk never ever end. The review in the Times concludes that if you are the type of person to be impressed by David Salle and his in-crowd pals, you will be charmed by this book; the Times is impressed by David Salle, and charmed, hence you should be as well.

Salle, emblematic boy wonder of the 80s New York art world, won critical and financial success with a prodigious output of paintings characterized by a layering of miscellaneous visual debris – e.g. candlesticks, African masks, meat, mid-century-modern furniture, male poets’ names – over images of depersonalized naked women. They are iconic paintings, the encapsulation of the lingering, though now ebbing, postmodernist ethos of cool irony, smirking indifference, self-satisfied self-absorbed nihilism. Salle’s paintings were (and are still) lauded for how they interrogate meaning, which is to say, asserting that meaning is passé, so too truth, everything is equally meaningless, phony; the sophisticated choice is to forego the hopeless, childish search for meaning and dwell instead in superficiality and introspective masturbation. Salle’s paintings are alleged to be interesting precisely because they are meaningless; they elude meaning and thus provide critics and others with a stake in voluminous babbling over art much opportunity to grope prolix toward an analysis, with a concerted focus on the formal. Much has been written about Salle’s use of collage, juxtaposition and superimposition, appropriation, the politics of representation, his inversion or coy repudiation of “art’s rules”—therein is the inventiveness and allure of his work, to a certain set in any case. It is art about art, an elitist onanism which, upheld as an appropriate, even righteous, fixation, has the salutary effect of justifying the detachment of the elite from every reality outside their own cocktail party shrimp canapé existence. With your head up your ass you are saved from bearing witness to the suffering of others. Injustice is as meaningless as everything else.

In the critical revel stimulated by Salle’s work – ongoing for 30+ years now – what routinely goes unassessed is the actual content of any given Salle painting. Here is a painting of a headless woman ass-up on an exam table with a tugboat toot-tooting out of her vulva; let’s talk about Salle’s use of fragmentation as technique, illustrative of the consumer-culture disintegration of coherent selfhood. And here’s a painting of a woman naked and bent over backwards with a crowd of men eating lunch between her thighs, an orange fiberglass chair jutting out from the other half of the canvas beside her, on level with the woman’s pubis, as if to indicate a shared function for both objects; let’s talk about how art’s function is to mediate between our private and public selves, let’s talk about the colors grey and orange. Mira Schor writes, “Salle’s depiction of women is discussed in terms of the deconstruction of the meaning of imagery, and in terms of art-historical references to chiaroscuro, Leonardo, modernism, postmodernism, poststructuralism, Goya and Jasper Johns, Derrida and Lacan—you name it, anything but the obvious.” 1

Exceptionally obvious in Salle’s paintings is the misogyny explicit in his representation of women’s bodies, dismembered, violated, made literally the butt of the artist’s highbrow jokes. It is a misogyny so obvious that it is below consideration. Only the prudish and feebleminded get hung up on it, imprudently foreclosing on “a much wider possibility of discussion.” 2 Feminist critics, like Susan Chadwick and Elizabeth McBride, who have charged Salle with contempt for women are cited in passing only in order to emphasize that Salle’s work is controversial – a selling point, furthering the artist’s reputation as irreverent bad boy, that stock figure – and then summarily dismissed, in favor of “deeper” discussions.

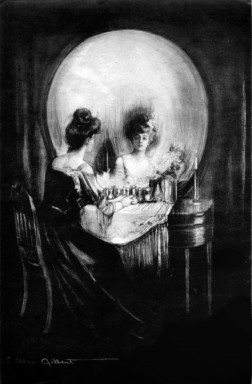

This failure of critics to question male artists’ images of women naturalizes and sanitizes the (ab)use of women-as-objects in man-made imagery, and by extension, man-made culture. It is taken for granted that male artists’ art will orbit “the female nude,” superlative image-object, desideratum, the epitome of Art itself, and the male artist’s brilliance glimmers in how he chooses to deploy the image of Woman, such that whatever uses he puts women towards, however he distorts or humiliates women’s bodies, it’s fair play; women are sacrificed in the name of Art. Woman is image and Man manipulates her; out of her image, the stuff of her, pictorial matter ripe for the picking, the man constructs meaning.

Although the postmodernist principle that guides Salle and his admirers avers that we are all swimmers submersed in a vast empty meaninglessness, there is nonetheless a hierarchy of meaning-manufacture: some are allowed to claim meaning, even if they do so only to affirm meaninglessness, while others have no claim and are to accept the meanings established by the authorities. Meaning is the province of men, the dominant class. David Salle, artist, man, is an authority; it is his place to explain to us How to See. He paints women: he tells us How to See Woman, for him a surface or container (many of his paintings feature women juxtaposed with cups, bottles, etc.) to function as vehicle for his own meanings. Women have no valid claim to meaning; when a woman writes that she sees Salle’s representation(s) of women as a mean-spirited degradation of women and the female body, she is shrugged off, for she is not seeing the painting how she ought to see it, as a man would. A woman lacks the capacity for lucid vision, since it is her role not to see but to be seen. Everything may be meaningless and artificial, but women’s subjectivity is the most meaningless conceit of all. This assumption precedes postmodernism: it is at the core of Western art. Thus the ubiquitous female nude, fiddled with more or less ingeniously, gorgeously or brutally, by generation after generation of male artist. Thus the dismissal of women’s objections to whatever variation of this fiddling, from Ingres’ plush bathhouse odalisques to the sleek and dead-serious yet juvenile, vacuous cruelty of David Salle’s vision of women, torqued in barren institution-gunmetal rooms, shirts pulled up over their faces, dunce caps strapped to their breasts as they sit blankly on rumpled beds. But this is the reality of male-dominated cultural production: men like David Salle write the manuals on How to See; women do not get to have a say.