Intellectual, artistic men do many things I would greatly prefer them not to do. One of these is deeming themselves “filmmakers” and making harassingly self-important movies with which they propose to capture the deepest-buried bleakest yet dazzling, gem-like truths of the human experience. Another diversion of the intellectual artistic male elite is buying access to women’s and girls’ (and less often boys’, even less often poorer men’s) bodies for use as masturbation equipment. It is not a pursuit unique to artistic men: the upper crust shares with less cultivated members of the master class a steadfast fascination with prostitution. Obviously men’s commodification of women into consumable goods is a passion more malignant than their production of pompous movies, since while one can ignore the movies – sorry, I mean: films – if one is disturbed by men’s domination, exploitation, cooption and comprehensive hijacking of female bodies and female lives, the devaluation of women into fuck-dolls for male amusement demands attention. Yet it is difficult to disentangle men’s cultural production (e.g. “filmmaking”) from men’s upkeep of the cultural institutions of male dominance (e.g. purchasing women). Because people make art about what interests them and as agents of patriarchy men are extremely interested in the reduction of women into sex-things to own & use, male filmmakers have gifted society with heaps of films about prostitution. The concept, I believe, is that the intrepid minds behind these films plunge fearlessly into the sordid morass, transgressing taboo to unearth the deepest truths of prostitution, or prostituted womanhood, or human sexuality. Actually, the lone “deep truth” revealed by these male-authored portrayals of prostitution is the profundity of self-serving delusion that permeates men’s view of prostitution, prostituted women, women generally, and sexuality itself.

Prostitution as it exists in male fantasy bears scarce resemblance to prostitution as it functions in the lived experience of prostituted women. Men’s films realize in flesh then light, color, sound male fantasy, not female reality. Why would we ever expect them to show us the truth?

It is a sacred misconception among MFA types that the more intellectual and formally experimental and outwardly radical an artist is, the more trustworthy he is as an authority on the nature of earth-lived existence. This strain of moviegoers would likely recognize the unreliability of Pretty Woman as a representation of prostitution—so commercial, so cliché, so sentimental! But what if it had been directed by Derek Jarman? Or Pasolini? Wouldn’t it then be bound to contain within some elusive interior vesicle a kernel of raw truth? The filmmaker is such an original, after all. We can assume he has an enlightened and progressive perspective on prostitution. Except, putrid as it may be, the male radical party line “enlightened and progressive perspective” is that there’s nothing wrong with buying women as sex objects, that in fact it’s enriching for both buyer and bought, and promotes a freer society, which suggests to me that fancy highbrow men’s fancy highbrow films are unlikely to prove a region of the arts populated by accurate fact-based depictions of the sex trade. However, I could be mistaken; maybe the great auteurs of modern cinema have not been egoistic chauvinist assholes spoonfeeding misogynist mythologies to upscale audiences. To find out, I subjected myself to a selection of the finer prostitution-themed films to ever flicker visions of whoredom across patriarchy’s arthouse screens, virtuosic offerings served up by some of cinema’s most venerated darling boys.

Vivre Sa Vie (1962)

Male Genius: Jean-Luc Godard

A film on prostitution in which a young and pretty Parisian shopgirl gives her body but keeps her soul while she experiences a series of adventures which bring her knowledge of all possible deep human emotions. — Godard, promotional copy for VSV

Anna Karina (who was married to Godard at the time—how like a man, to pimp his wife) plays Nana, a young Parisian woman who deserts the dreary domestic burden of husband and son for dreams of a more venturesome and independent life. She speaks of becoming an actress. Meanwhile she works as a shop assistant at a record store, but the job is drab and ends aren’t meeting in any case and then one day she discovers that men will buy her for sex if she lingers on the sidewalk. Thus Nana enters prostitution. Nana’s character is a composite of canonical prostituted women: her name a reference to the eponymous ill-fated courtesan of Zola’s novel Nana (1880), her sleek black bob recalling Louise Brooks in her roles as similarly fallen women in the silent films Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl. These allusions, in addition to announcing Godard’s cultural savvy, foreshadow a less than sunny conclusion for Nana, though since she is a sexualized female advancing through a male-charted narrative we never had any cause to anticipate a happy ending for her. Despite being doomed, she retains the sweet childlike optimism that men find so endearing in women. She smiles and giggles, she dances, she advises people to look for the beauty in things to stave off depression. She talks philosophy; like a consummate girl she defends ardor: “Shouldn’t love be the only truth?” She takes a lover. The film closes with Nana lying crumpled dead in the street, shot in a skirmish between her pimp and other pimps to whom he intended to sell her. The men drive away. Of the abrupt arbitrariness of her demise a film critic explains: “the point is that it’s pointless.”[1] (Female death is loveliest when pointless! Like life. Life is pointless. Ah, philosophy!) Susan Sontag called Vivre Sa Vie “a perfect film,”[2] though she clarified: not one about prostitution. Prostitution is not the film’s subject but its guiding metaphor—“a crucible for the study of what is essential and what is superfluous.”[3] (Women’s lives are most compelling when appropriated as vehicles for men’s weighty musings!)

Sontag was correct in that Vivre Sa Vie is not about prostitution—an artist as high-minded as Godard would never devote his talents to so prosaically topical a project, and most of the art that men make about women is not really about women but men (“humanity”), with the women operating as symbols for concepts more worthy of extended consideration (e.g., “the human condition”). Nonetheless, the film represents prostitution. At the risk of exposing a crass indifference for the metaphysical, it’s my point of view that the representation of prostitution in Vivre Sa Vie requires scrutiny, no matter how metaphorical it may be, because in its representation it indicates several key elements of the male fantasy that has colored our cultural understanding of the phenomenon. While Godard’s film does not show prostitution to be a joyous zone of female experience, but instead a rather melancholy one, it does imply that prostitution for Nana is not much worse than any other job a person might have; the malaise of it is that it’s as boring, repetitive, and thankless, as all modes of labor are in a consumerist culture. Nana smokes a cigarette looking cool-eyed over the shoulder of a john as he embraces her. Day after day she undresses, she washes, she falls into bed, a man climbs on top, she zips her dress back up, she returns to the street. It is probably true that selling sex can be dull. What is also true, and absent from the film, is that boredom is not the primary source of prostituted women’s angst. Starvation, for example, may be more worrying for many prostituted women around the world. Continuous misogynist contempt and harassment and routine physical violence are also apt to be angst-producing. All of the buyers in Godard’s film are gentlemen seemingly in pursuit of a quickie between business meetings. They are cordial, if taciturn; in their use of her body none of them beat Nana, none of them rob her. Nana is not vigilant with concern for her safety. Real women in prostitution must always be, because men who buy women are the same men who abuse women, and men abuse the women they buy.

Godard additionally intimates that Nana has found personal freedom in prostitution, a welcome escape from the suffocation of her “bourgeois marriage.”[4] Gloomy as it may be to peddle her body to strangers in rented rooms, at least now she is a free woman. I would say: out of the furnace, into the fire. In marriage, you are owned by one man; in prostitution, you are shared among many. In either case, you need a man to live. Men have been working the “freedom” angle forever, trying to sell women on the flawed conceit that to depend on men’s desire to use one’s body for one’s livelihood constitutes the apex of female independence. It’s especially nonsense since women in prostitution around the world are enslaved by pimps and brothel managers, who hold the women they sell in debt so they’re trapped and then expropriate their earnings. Even for those prostituting without a middleman, the typical route of entry into the sex trade is destitution directly resulting from the systemic manufacture of female poverty. Prostitution is a symptom of and a model for the oppression of women in male supremacist society; it contradicts freedom, save for men’s freedom to assert their collective proprietorship of female bodies. Godard only encroaches upon a halfway accurate illustration of this reality when he has Nana killed by men who do not care about her at all. Men murder prostituted women all the time. They own them; they can do what they want.

Though Godard may have represented Nana’s life as a prostituted woman as a trudge rather than a romp, it was still an idealized, romantic trudge, a tragedy. In Vivre Sa Vie, we see prostitution as a beautiful way for a woman to be sad, and a sad way for a woman to be beautiful. Godard says Nana gives away her body but keeps her soul, which is a beautiful concept, isn’t it? Her soul is beautiful because it is childlike, wide-eyed, pure. She gives away her body until she is all soul, its pearl-like ethereal beauty stripped bare and palpitating, until she has no body: she dies. The problem for me is that I question the usefulness of a beautiful soul to a dead body.

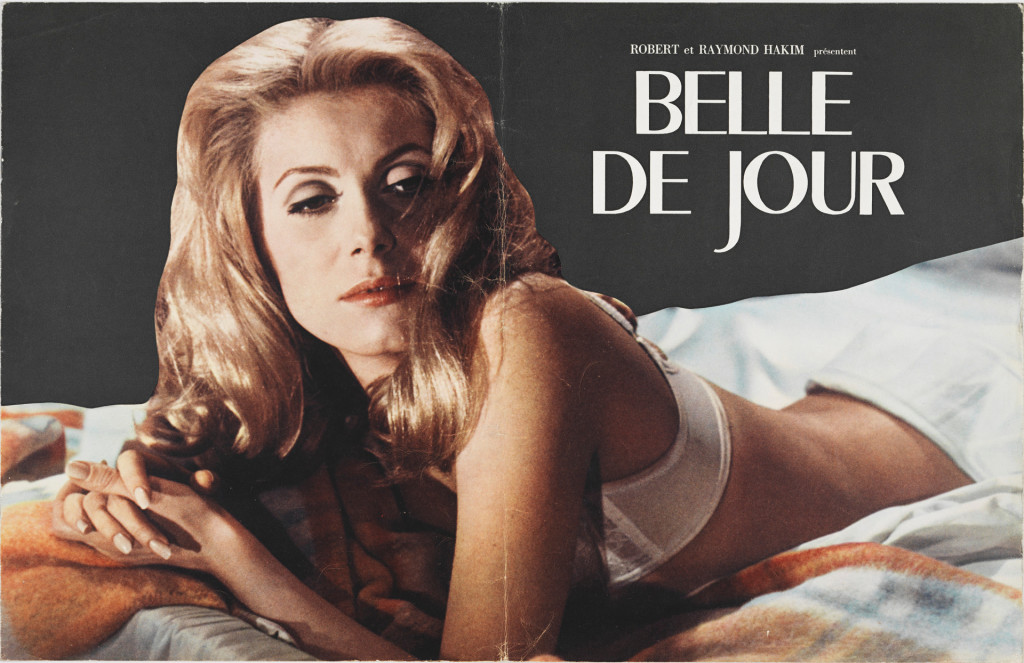

Belle de Jour (1967)

Male Genius: Luis Bunuel

Riding in a horsedrawn carriage down a road through some autumnal country estate prim with hands folded in the lap of her scarlet tweed suit Catherine Deneuve is a glacial mannequin sitting stiff next to a man, not looking at him, looking straight ahead with an expression of genteel but total impassivity. The man beside her is Pierre, her husband, and he loves her; she concurs she loves being with him, but she is not receptive to his physical affections. He moves to embrace her; she rebuffs him. Pierre yells for the coachmen to halt the carriage and the horses stop and together the three men drag Catherine Deneuve along the ground to a tree in a clearing where they tie her and rip her suit jacket to bare her back. Catherine Deneuve struggles and sighs until the coachmen start striking her with their horsewhips and then she appears in a state of ecstatic beatitude; her entire body relaxes. Pierre grants the help permission to rape her. This scene, which opens Belle de Jour, plays out only in the mind of Catherine Deneuve’s character, Séverine, an aloof housewife destined to blossom into a whore. It is her fantasy, and she has another: again she is tied up, this time in something like an outdoor desert stockyard dining hall, while Pierre and a male friend of the couple hurl mud and insults to splatter defiled her white gown. They call her a slut, et cetera—it’s pure rapture. Belle de Jour is a film about female sexuality, a subject that Bunuel as a man was assuredly qualified to comment upon. It is based on a novel by a man[5], who was also doubtless an authority on female sexuality. What man isn’t? Naturally, in this exploration of female sexuality, the heroine is drawn by the currents of her fantasies and fate into prostitution, where at last she finds fulfillment.

Though Séverine is too icily expressionless an automaton throughout the film’s duration to ever be read as “happy” per se, the thrust of the plot is that prostitution suits her. The daily degradation of being used. The just-lying-there-like–sack-while-some-man-maneuvers-your-body pleasure of utter passivity. She is satisfied. Pre-brothel, an absence gnawed at her, an unmet need the throbs of which spurred intrusive daydreams of whips and mud and humiliations by men. Prostituted, Séverine is whole. She is a woman, in her natural, unrepressed state a whore.

Outside of the male imaginary, prostituted women would prefer to be doing something else. Studies in which women were asked if they would like to leave prostitution, and the majority answered yes, they would, pointing to the rather minimal desirability of selling sex as an occupation, much less an afternoon recreation, for most women[6]. It is in fact atypical for a woman such as Séverine, a well-tended wife with an apartment full of Faberge eggs, to seek out a side gig as a prostitute. Men will be disappointed to hear this, since they are enamored of believing that women get their thrills selling sex, that we are, like Séverine, compelled toward prostitution by dint of our feminine essence. I’ll repeat that women are compelled toward prostitution by dint of economic necessity and lack of alternative viable options, perhaps homelessness, perhaps substance addiction. A smaller number of women, in happier material circumstances, are compelled by the goading of male supremacist propaganda (e.g. Belle de Jour) and commence to sell their bodies to men believing that prostitution will be exciting//satisfying//erotic. This camp constitutes a microscopic but very vocal (the voices of the privileged are always loudest) minority of prostituted women.

Skimming through critical reviews and scholarly reflections on Belle de Jour, I observed that in general people are under the impression that Séverine is driven into prostitution by the force of her uncontainable masochistic desire for degradation, which serves to emancipate her from the tepid repression of her married life with Pierre[7]. As Vivre Sa Vie told the story of a woman’s existential liberation from the stymying convention of marriage, Belle de Jour tells of a woman’s erotic liberation, with the shift from marriage to prostitution classified as the superlative gesture of sexual self-governance possible for a female. It’s basically a feminist film: Séverine knows what she wants and she goes after it. She wants to be degraded and roughed up by men; automatically men’s degradation and roughing up is revamped into liberatory abetment. [ commence the “YOU GO GIRL” chant now ] Isn’t it convenient that so many men are willing to liberate women in this way? It’s a wonder the patriarchy is still standing today what with all the liberation that’s going on in the international sex trade.

These reviewers//scholars would seem to be coming into Belle de Jour with a specific pre-gelled take on prostitution – whereby it is the woman’s way to deliverance from repression – since the film’s narrative does not support their interpretation of events. Prostitution is not presented as a desire pursued but rather an ineluctable destiny for Séverine. She actively pursues nothing. Her dreams bespeak an absence, an inner need; she did not craft them of her own accord—they erupt in her. Clues are placed in her path to convey her toward her fate. Like the mannequin-automaton she is styled after, Séverine glides smoothly unperturbed along the tracks of the preordained from marriage to the brothel. It is a similarly groundless re-framing to assert that Séverine was “unsatisfied” by her stuffy asexual (bourgeois) husband. In the film Pierre expresses interest in having sex with her and frustrated disappointment when she shrinks from him. She shrinks because she is frigid, her sexuality is as yet undiscovered, it has not yet been awakened, because she has not yet become a prostitute. In Belle de Jour, Séverine is hardly an empowered woman expressing her agency as an individual by following her forbidden lust for suffering into the brothel. Rather, she is a woman actualizing herself as Woman: a whore, who suffers and loves it.

Male delusion holds that women are by constitution and personality prostitutes, that we are so wholly sexual that to sell sex is the highest calling of our kind, that the only liberation we need is sexual liberation, which we can access through surrender to our passion for being used. How predictable that a man making a film about female sexuality based on a male-authored book about female sexuality would champion this myth of innate female whoredom. How pitiful and how terrifying audiences accept it as the truth.

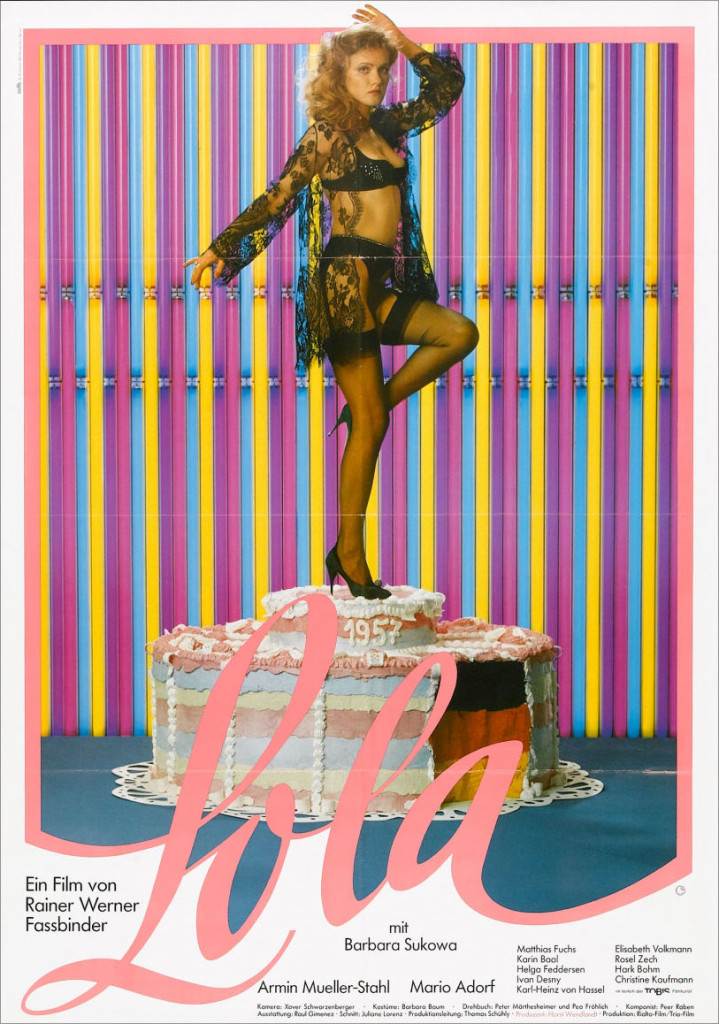

Lola (1981)

Male Genius: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Once again we are treated to a film about prostitution that is not about prostitution. Whereas for Godard the serious crux was the human soul, Fassbinder’s serious concern is capitalism. The brothel symbolizes the apex of capitalist corruption, a seedy red-velvet-lined hole where men’s ideals go to die. It seems we’ve got another searing critique of bourgeois existence: “The point, of course, is that they’re in a whorehouse all the time, that bourgeois society is a whorehouse.”[8] The titular prostituted woman, Lola (played by Barbara Sukowa), is not so much a character as a narrative device. And what is her function? She incites an Honest Man’s downfall.

Lola is the star prostitute//cabaret showgirl at a brothel//nightclub owned by Schuckert, a greasy and brutish cigar-smoking tycoon-caricature of a real estate developer who, coincidentally, also owns Lola: he calls her his “personal whore” and funds her existence, as the father of her young daughter. The brothel//nightclub is frequented by all the powerful men in town (including the Mayor), who we observe guzzling champagne, pawing at the female merchandise who circle them giggling giddy in black satin lingerie. We are thus made aware that this is a town where shady capitalist corruption reigns. Then a new man arrives: Von Bohm, the upright building commissioner. He is very impressive, because he has principles; he is a “moralist,” as the other powerful men deem him with a sort of impressed irritation. Not the type to visit the brothel. When Lola hears word of Von Bohm, through the men at the club and through her mother, who is his housekeeper, she is miffed because everyone keeps saying he’s not a man for her, the clear implication that she’s too low-class for him. Consequently, to prove them all wrong, she sets about seducing him. Lola dresses up in Good Girl polka dots and hats and white gloves and pretends to admire Asian art (she noticed a Ming vase in his house while visiting her mother there) and sings hymns to win his heart. Because even the most principled men are helpless against a siren’s formidable charms, she is successful in her mission: Von Bohm falls absolutely, idiotically in love with her. His love is battered, however, when he discovers she is a prostitute and Schuckert’s mistress. He goes on a bender of indignant rage, television watching, muckraking efforts to expose the town’s capitalist corruption, anti-war protesting, and alcoholism until finally he breaks down and visits the brothel to buy Lola. He still loves her, he marries her, she wears white, her daughter has a real father now—it’s all quite heartwarming. And of course he will approve whatever building projects the powerful and corrupt propose henceforth, since his desire for Lola has dissolved his morality. Lola, meanwhile, despite the ivory wedding gown and her cozy new social status as a Lady, is still a whore, permanently tainted: in the final scene, on the day of her marriage, while her new husband is out for a walk, we watch Lola readying to go to bed with Schuckert. Enjoying her reflection in the mirror she says she is an expensive mistress—and that’s just the way it should be. Schuckert gives her the brothel as a wedding present. She is so happy; now she has everything her amoral man-eating heart could desire. There will be no making an “Honest Woman” out of her.

In the candy-colored bordello that is corrupt capitalist bourgeois society, all women are whores. They may tease at yearning for love and a life outside the brothel, but it’s a sham; mercenary to the marrows they long merely for the veneer of respectability, which as an accessory grants social privilege, leverage; there is no redemption for women, and we desire none. We are whores, the pricier the better, and that’s just the way it should be. Men are powerless before us, in our boudoirs they fall to their knees at our silk-stockinged feet. In a corrupt society, a whore is a woman who gets hers. Such is the illuminating thesis on prostitution advanced by Fassbinder in Lola.

The idea that prostituted women are in a position of power over the men who purchase them is a popular reversal of the self-evident reality that, if you are selling sex to men to earn money to sustain your existence, you do not have power over those men; they have power over you, because they are the ones with the money you need to live. Men do not need to have impersonal sex with commodified women to survive. It’s a privilege and a luxury, but not a fundamental necessity. Women, however, do need money to live. Power is hard to come by for most prostituted women: many do not have the power to choose their clients, they do not have the power to choose what their clients do to them, they do not have the power to protect themselves from men when they get violent; it is only seldom within their power to get out of prostitution if they are unhappy. Men’s exaggeration of women’s power is a central strategy in the obfuscation of the patriarchal structure of society. To represent prostituted women – who are impoverished women, abused women, enslaved women – as women who’ve worked the system to ascend to dominion lording it over males is the tactic pressed to its fraudulent limit.

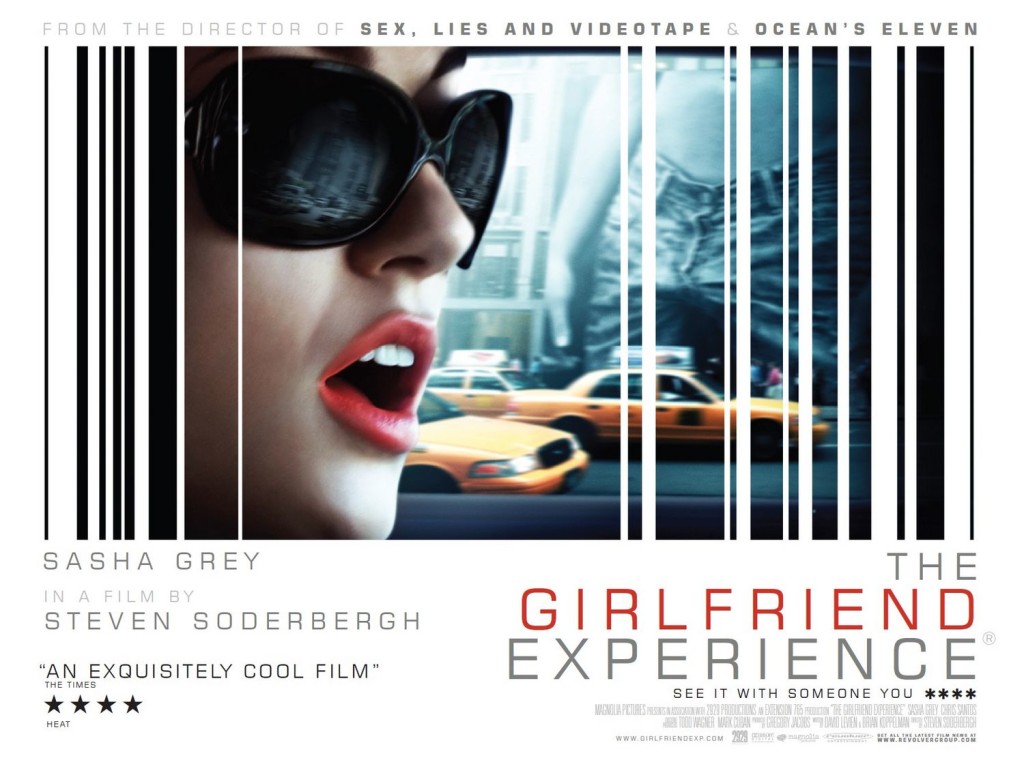

The Girlfriend Experience (2009)

Male Genius: Steven Soderbergh

The Girlfriend Experience is another film that uses prostitution as metaphor fodder for a meditation on capitalism-induced social decay, but unlike Fassbinder, Soderbergh as its director hasn’t feigned to care much about his topic; he couldn’t even muster the self-righteous mean-spirited mordancy that Fassbinder applies to the task. A blistering critique The Girlfriend Experience is not. Indeed, it is better compared to an 80-minute long shrug, with an occasional palsied twitch of smirk. It is so blasé about itself and its subject matter and its characters that I am mystified as to how//why the film ever made it to completion. My suspicion is that the aim of the oppressive air of listless affectless apathy was to lend the movie credibility as a realist work, but the method was abortive—no level of tedium transmutes bullshit to verisimilitude. A more effective approach would have been to realistically portray prostitution and its reverberations in the lives of prostituted women. Doubtless this alternative never occurred to Soderbergh and crew. No matter how worldweary men may be, without fail they perk up to attend to the critical business of counterfeiting female reality.

In The Girlfriend Experience, Sasha Grey, “The Thinking Man’s Porn Star,”[9] plays an upscale escort (expensive euphemism for: prostitute) who goes out to chic restaurants with wealthy men and rides home with them in hired cars to their sleek apartments and then listens to them fret about the state of the economy or receives financial planning advice while she sits on their beds bland and docile staring and nodding in various expensive lingerie ensembles, which she details in her diary subsequent to each session, along with insights into the outer layers of her apparel. She is ambitious, an avid go-getter; she is eager to expand her business. We follow her as she meets not only the men who buy her – her “clients” – but men she hopes can facilitate the fast-tracking of her career: a man who’ll design her a website and optimize its search-engine results, a man who’ll write a positive review of his services if she gives him a complimentary sample of the goods, a man who has launched other escorts to sex work stardom. Inexpressive to the point of appearing embalmed she floats from investor to investor, promoting the start-up that is herself. She is an entrepreneur. Her live-in boyfriend encourages her: “You’re the best at what you do!” He is proud, and he understands the nature of her work, because as a personal trainer he also deals in faux-companionship and ego boosting. The escort seems primed for an unstoppable surge upward to the highest echelons of whoredom, until she makes the error of falling for a screenwriter (named David, played by an actor named David, who also co-authored the screenplay…coincidence? or conceitedness?) who buys her for a weekend in NYC and who she comes to believe for astrological reasons may be her soulmate. She is so skilled at her trade that she dupes herself into believing her own act: that she is his girlfriend and he could love her. He doesn’t love her; he loves his wife and children and goes back to them and momentarily a quavery glimpse of human emotion shows through Sasha Grey’s character’s inscrutable husk. Then she wises up, quits sniffling, and jumps back in the game, like a good little hustler should. The End.

The Girlfriend Experience is an exceptionally ugly, stupid, enervating, and unlikeable film. Watching it was like having the breath slowly sucked from my lungs by a chill-lipped specter hovering over my sofa; I felt less alive afterward and I cannot disrecommend the film enough. Do not put yourself through this. You could do anything else and have a better time.

Except, perhaps, for actually living two hours as a prostituted woman. Unlike the escort in Soderbergh’s movie, most prostituted women are not “entrepreneurs”—survival, not market diversification, is the goal. Prostituted women do not make $2,000 hourly or whatever looking supportive in La Perla thongs whilst men prattle on about the upcoming election. They suck men off. They jerk men off with their hands. They lie down in motel rooms and on wipe-down brothel mattresses and concentrate on other things until the men who buy their bodies ejaculate into the orifice of their choosing and take off. A corresponding reality is that men who buy women are not on the prowl for the “the girlfriend experience,” for someone with whom to eat sushi at pricy restaurants, who can coo doting reassurances when they start to get squirrely over their portfolios or loveless marriages[10]. Men who buy women buy women to fuck them. To use a woman’s body. To possess a woman, to experience male power, because with their money they can purchase a woman and control her. I do not doubt that any manner of additional ego-petting a prostituted woman might provide would be appreciated by her buyers, as an extra treat – men have an insatiable appetite for admiration – but the rapport is supplemental, not requisite. A man who buys women needs compliant warmish flesh he can own for an hour equipped with a wet hole or two he can thrust his penis into. That’s the bottom line of prostitution.

//

To briefly summarize: since none of the films highlighted grinding poverty, marginalization, constant violence from sex-buying men, entrapment by pimps//traffickers, post-traumatic stress, histories of incest and abuse, or substance addiction as the major defining realities of prostitution, but instead presented prostitution as “just a job” fitting enough for a woman, altogether natural if not her bliss and consummation (as in Belle de Jour), and potentially lavishly lucrative, it is apparent that all four are premised in the male fantasy of prostitution rather than its reality. I would also like to note that in each film, the prostituted heroine was a white woman. This is another aspect of the fantasy, the women’s privileged whiteness invoked to distance prostitution from the structural inequality and exploitation that spawn it. Internationally, more women of color are in prostitution than white women, because women of color are poorer, more thoroughly depersonalized in white supremacist society, and it is poor women of colonized nations who populate the world’s brothels, not middle class white women understimulated by their hum-drum bourgeois existence. Also: in none of these films is the prostituted heroine a child. Most women enter prostitution when they are 14, 15, 16 years old. In none of the films is the sex between the prostituted woman and her buyer portrayed as sexual violence against women. Sex trade survivor Rachel Moran describes the sex of prostitution as paid sexual abuse—the monetary exchange does not mitigate the violation or the violence entailed in the encounter, or the damage it inflicts[11].

In each film, prostitution is represented as a choice: a woman makes a conscious decision to be a prostitute, of her own free will, uncoerced. This, finally, is the grossest distortion of all. Women seldom become prostitutes under conditions where free will is familiar to them (in as much as it can be familiar to any woman). Women do not prostitute themselves: patriarchy prostitutes women. We are all coerced, and movies like Vivre Sa Vie, Belle de Jour, Lola, and The Girlfriend Experience are instruments of mass coercion: stylish fictions crafted by men to convince us that underneath everything we’re whores, extant to get fucked—our vocation.

The truth is that no woman on earth is a whore.

//

APPENDIX:

Recommended Films on Prostitution//Sex Trafficking:

Buying Sex, 2013

Tricked, 2013

The Price of Sex, 2011

Who Cares, 2012

Whore’s Glory, 2011

Lilya 4-Ever*, 2002

*this is not a documentary & it is directed by a man, but its image of prostitution is (miraculously) neither romanticized, sterilized, nor male-serving.

//

NOTES:

[1] Perkins, V. F. “Vivre sa Vie.” The Films of Jean-Luc Godard. Ed. Ian Cameron. New York: Praeger, 1969. 32-39.

[2] Sontag, Susan. “Godard’s Vivre sa vie.” 1964. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1966. 196-208.

[3] Sontag, 1966.

[4] Mathews, P..”The Mandatory Proxy.” Biography 29.1 (2006): 43-53. Project MUSE. Web. 12 May. 2016.

[5] Kessel, 1928.

[6] For example, in a survey of 119 women working as prostitutes through escort agencies or on the street in Phoenix, AZ, 94% stated they’d prefer to leave prostitution for another job with similar pay. (Kramer, 2003, p. 195). In Paid For, Rachel Moran’s excellent memoir of her experiences in prostitution, the author writes: “In the seven years I spent as a prostitute I met innumerable prostitutes and I have had friends in the trade for more than half my lifetime, and I have never met a prostitute who didn’t wish she was doing something else.” (2013, p. 152)

[7] Melissa Anderson supplies a representative example of the prevailing analysis in an essay for The Criterion Collection when she sums up Belle de Jour as “the story of Séverine, a deeply disenchanted haut bourgeois Paris housewife who finds erotic liberation through byzantine psychosexual fantasies and part-time work at an upscale brothel” (2012).

[8] Denby, David. “Falling in Love Again.” New York Magazine 23 August 1982: p. 88.

[9] Khakpour, Porochista. “The GQ&A with Sasha Grey.” GQ.com. Web. 12 May 2016.

[10] Despite what Roger Ebert might’ve thought: “By paying money for the excuse of sex, they don’t have to say: I am lonely. I am fearful. I am growing older. I am not loved. My wife is bored with me. I can’t talk to my children. I’m worried about my job, which means nothing to me. Above all, they are saying: Pretend you like me” (2009). Nice try! While it certainly makes sex-buying men look slightly more pseudo-decent to recast them as lonely and emotionally vulnerable human beings chasing lost intimacy, and maybe it’s the case sometimes, such does not characterize the greater part of sex-buying men. We need not expend overmuch of our sympathy on the johns of the world.

[11] Moran, Rachel. Paid For. 2013. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015. p. 106-108.