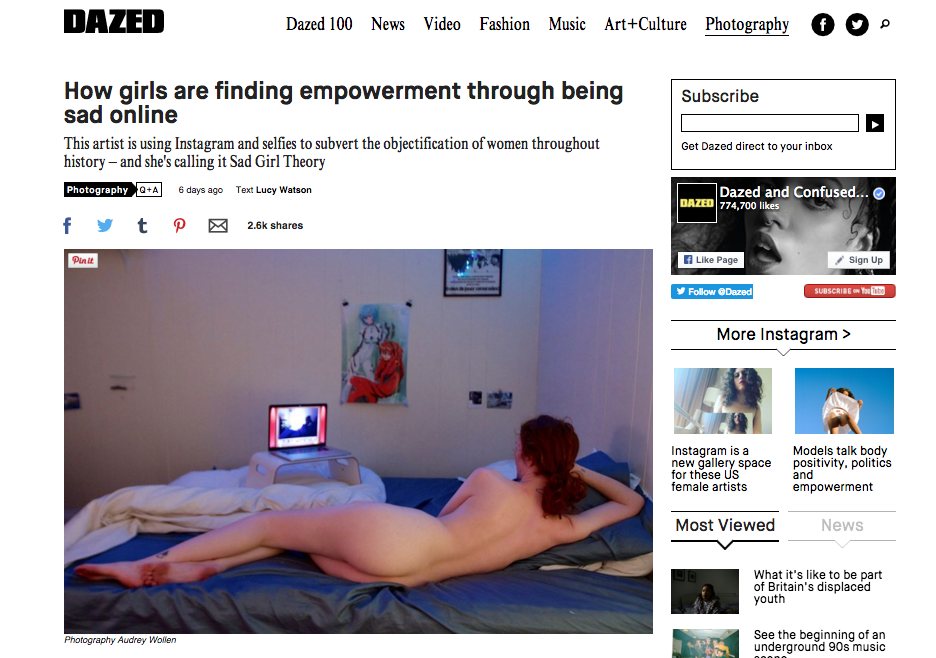

Dazed Digital, the online corollary of the fashion//art//culture magazine Dazed & Confused, published an article last week introducing the world to a new form of “feminist art” that made apparent how dazed, confused, bewildered, addled, muddled and generally clueless this publication and its readership are as to the meaning of the terms feminism and resistance. The subject of the interview is Audrey Wollen, a rising young artist whose major export is photos of herself pouting or dead-eyed, sometimes dressed in fashionable outfits, sometimes fashionably slumping out of her outfits, posted to Instagram. Wollen informs us that these photographs represent her exploration of “Sad Girl Theory,” a peculiar new model of feminist practice which proposes that by embracing the pain of growing up female within patriarchal society – and all of the degradation, the victimization, the constant fear, the engrained self-doubt and self-hatred that entails – we as women can use our “sorrow and self-destruction” to reclaim agency over our “bodies, lives, and identities.”

Since self-destruction by definition leads to a relinquishment rather than a reclamation of one’s body and one’s life, it is difficult for me to imagine how, exactly, we as women are going to manage the task that Wollen has proposed for us.

Of course, suicide would be at the extreme end of the “Sad Girl” catalog of possible acts of feminist resistance; one hopes there are less terminal means of dismantling patriarchy via purposive melancholy. And indeed yes! Based on a review of Wollen’s art as displayed on her Instagram, our options include: glum Sailor Moon cosplay, eating sandwiches naked in bed, standing expressionless alone in public in stylish sunglasses.

Being personally unsure how these approaches would work out for women as a subjugated sex class in our effort to extricate ourselves from male supremacist oppression//exploitation//brutality, I turned to the oracle that is the collective for counsel. We read the Dazed Digital article and we asked ourselves: is lying on the ground downed by the mortal anguish of womanhood and recording that experience of lying there in misery via selfie dissemination online a potent mode of feminist resistance for these sick sad times? is a pout the best we can muster at this point? *are* girls in fact finding empowerment through being sad online??

IN ANSWER:

♡

CD: I can only look at Audrey Wollen’s ‘art’ with abhorrence: using the objectification of women (herself in vapid nude selfies) to show how our patriarchal society objectifies women (especially in art) is wrong because she is merely reinforcing the stereotype. Maybe if she put a man in her place or a woman who does not fit the stereotypical female figure her intentions might appear to try to aide in women’s fight for equality, but she would still be perpetuating the myth. Wollen is defining femininity and the female in patriarchal terms. She is contributing to the problem. I’m definitely not saying that nudity should be censored, but using the female figure in the same way that male artists objectify women only gives them and others the stamp of approval to do worse things—to belittle women, not take women in the workplace seriously, make women sex slaves, rape women, abuse women….

This faux feminism, confuses the rest of society and makes would-be supporters distance themselves from feminist ideology and the movement towards equality. When I was younger, I found myself having negative reactions towards self-proclaimed feminists and writers. I also thought if I ignored sexist problems they would disappear. I’m writing now because I’m fed up and I want change. I finally started to read real feminist literature such as: ‘Our Blood‘ by Andrea Dworkin, ‘Witches, Midwives and Nurses‘ by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, ‘Women’s Rituals‘ by Barbara G. Walker, ‘Medical Muses‘ by Asti Hustvedt and others. ‘Sad Girl Theory’ is the excuse of a lazy privileged woman who defines herself on the patriarchy’s terms. A woman does not have to limit herself by being either a sad, weak girl or a bitch. Life is hard and being treated like a minority when women are a majority (half of the population) is hard, but quoting Tupac, ‘They win when your soul dies.’ Francesca Woodman and Virginia Woolf would kill themselves again if they read this article about Audrey Wollen and how she tries to align herself with them. On a positive note we are having a discussion about feminism because of this woman’s artwork. I’m aware that female nudity did have a feminist role in artwork in the 1970s and 1980s. It does not have the same meaning today. I’m an artist and unfortunately the art world is still a boys’ club. Of course these faux feminist artworks and others like it are praised and accepted into the male artists’ sphere, because it reinforces men’s position on top. Female artists need to rise above the male artist’s gaze. We’ve got to keep our heads up.

♡

♡

JC: At first, I was surprised by Audrey Wollen’s Sad Girl Theory as a reaction to the the positivity of mainstream feminism. Have Sheryl Sandberg and Beyonce finally displaced the hairy angry lesbian as top straw construct? Well, no. But Wollen is onto a new wave: lying supine, sometimes in clothes, a genre you may recognize from every fashion magazine and plenty of commercials.

♡

KG: I don’t think it’s a valid artistic practice to just “do what you actually feel like” when everyone living under patriarchal culture has been conditioned to “feel like” doing things that hurt (or advocate hurting) themselves and others. It may be “dangerous to have your radical politics caught in a cycle of reaction,” but it’s even more dangerous to excuse yourself from self-criticism and let your work prop up the system you ostensibly want to destroy. The work that Wollen apparently feels like doing is basically to advocate for women’s self-harm and suicide, and I can’t really imagine what machinery she thinks she’s jamming, or what patterns she’s supposed to be changing, by adding to the ever-growing collection of photos of women’s bruised buttocks on the Internet. Presenting such images as if they exemplify feminist rebellion might help her feel better about what she’s doing for a moment, but for everyone else watching, it only reinforces the misogynistic concept that women exist to be hurt.

Audre Lorde said that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house“; Wollen, on the other hand, insists that “we can use the products of the patriarchy as tools to dismantle it.” Well, as Lorde points out in the speech from which her famous quote came, the master does still furnish some women, who meet his standards, with a modicum of shelter, and for them, naturally, his tools would seem like the only ones available – or the only ones they really needed.

At the end of the interview, Wollen leaves us with a final thought to mull over: “what if the naked horizontal girl wasn’t a symbol of subordination, but a symbol of rebellion?” “What if,” indeed? What if restaurants paid you to eat their food? What if we all walked around on the ceiling instead of the floor? What if ostensibly intelligent and creative people all spent their time thinking up new ways to cast the status quo in a more favorable light, instead of trying to change it?

That last one isn’t hard to picture. Instead, let’s try to acknowledge women as real humans rather than symbols or mythic figures, and their suffering not as some abstract cosmic force but as the result of actual harm done to them by actual people (mainly men). This is harm we should be working to prevent, not to encourage or accept as the natural order.

♡

Each of these “Sad Girl Theory” Queens incurred lasting damage as a female raised in a male-dominated society (even if only a mythic one, as in the case of Persephone). Because they were hurt, they were sad, and their sadness made it difficult to live; because their lives were hard to live, they died young. The only exception of course is Persephone, a fictional character dreamt up by male weavers of myth. If she had been a real person, maybe she would have overdosed on barbiturates as well, like her more modern sisters. As crusaders against the patriarchy, resisting through misery as Wollen espouses, these women lost: tyrannized and reduced and abused and traumatized in contact with permeating male power, Judy, Marilyn, and Frida were induced to exit the world. We lost them. I mourn them I do not know how to celebrate their deaths as resistance because I think if they’d been resistant or if their resistance were effective maybe their lives could have been different, less tragic. Audrey Wollen is right about one thing: being a girl, or being a woman is very hard, and it is unimaginably painful. But she is wrong to promote acceptance of that pain as our fate. She is wrong and also callous, also irresponsible, to imply that the suicides and slower self-decimations of her Tragic Queens constitute an expression of female agency.

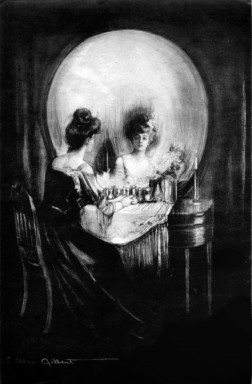

Sorrowful, fading women have long been glamorized to make wilting an alluring option for girls in a social reality designed to drain us of all vitality, will, self-efficacy, self-love, selfhood. Thus, if “Sad Girl Theory” were actually a feminist theory it would problematize women’s sadness and impulse to self-harm under patriarchal rule, not aestheticize it further, as it has already been aestheticized, romanticized, and sexualized throughout history. There is a reason why girls are fascinated by Marilyn Monroe and that is because we are granted women like her as objects of fascination, because we are raised only to decompose into nothingness, human voids, so men can fill us and use our bodies for their own purposes. We learn from Tragic Queens that there is no hope for us; if we try to be somebody, we’ll fail, and no matter how beautiful we are we’ll still die alone, because somehow this is all there is for us. We do not learn from them how we might thrive. We can accept the education and the pantheon of self-destructive role models men have provided us as roadmaps to our own dissipation or we could spurn masochistic fantasy in memory of our lost sisters – Judy, Marilyn, Sylvia, Frida, Virginia – trapped within the archetype of the Sad Girl, putting our pain to work as an engine not an anchor, and we could stand up instead of lying down, not discarding our sadness but driven by it. Fighting for a place to live, for our lives, not dying. That would be feminist resistance.

♡

Further Recommended Reading _